Power Through Pressure: Mechanisms of Hard Power in International Relations

Hard power is the ability to use carrots and sticks to get what you want - Joseph S. Nye Jr. (2011)

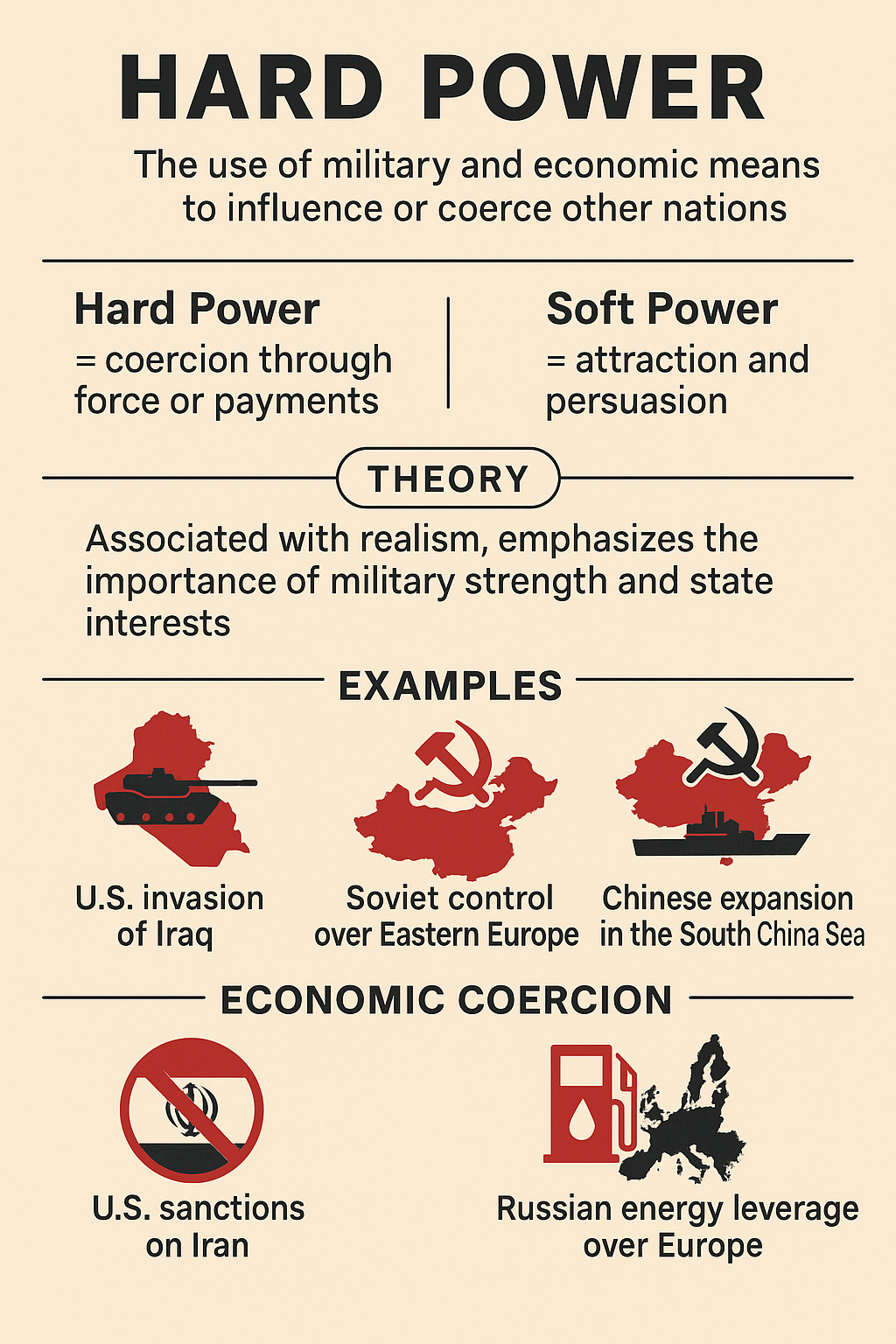

In the world of international relations, states use a variety of tools to influence others, assert their interests, and secure their positions. One of the most discussed concepts in this realm is Power. Power in international relations is the ability to make other actors do what they wouldn’t do otherwise. With the recent attacks by Israel on Iran, it is worth exploring the concept of Hard power, contrast it with Soft power, and illustrating it in action in global politics through some examples. This terminology will enrich the reader’s understanding of this and other geopolitical events.

What is Hard Power?

Hard power refers to the ability of a country to influence others' behavior through brute force, primarily via military or economic means. The concept gained prominence when Joseph Nye, a Harvard University political scientist, introduced the concept of Soft power in the late 20th century. Hard power operates through mechanisms of coercion: compelling another state to act in a way it otherwise wouldn’t, under threat or promise of tangible rewards or punishments.

Typical instruments of hard power include:

Military force: invasion, deterrence, or threats.

Economic pressure: sanctions, trade embargoes, or financial incentives.

Diplomatic isolation: cutting off alliances or recognition.

In contrast to persuasion, hard power relies on fear or material gain. It is blunt, clearly visible, and immediate in impact.

Contrasting with Soft Power

While hard power coerces, Soft power attracts. Soft power is the ability to shape the preferences of others through appeal and attraction, rooted in culture, political values, and foreign policies seen as legitimate or morally authoritative.

In simple terms:

Hard power = force and money.

Soft power = ideas and values.

Where hard power might involve sending tanks across a border, soft power might involve development aid, media influence, cultural exports, and things that win the hearts and minds of foreign populations.

A related term is Smart power which is the strategic use of both hard and soft power in combination—employing carrots and sticks as needed.

Realism

This categorization of types of power is best understood in the framework of Realism, one of the major schools in International Relations. Realism posits that the international system is anarchic, where actors seek power to secure their interests and primarily care about their survival. Under realism:

States are unitary, rational actors.

Military capability and economic strength are central to national power.

Alliances, deterrence, and wars are tools in a perpetual struggle for power.

From this perspective, Hard power is not just an option but a necessity in a world without a global police force. Two main thinkers in this tradition are Hans Morgenthau, who emphasized the centrality of power in politics, and Kenneth Waltz who emphasized that the structure of the international system forces states to act in certain ways.

In contrast, Idealism and Constructivism suggest that power isn't only about force. Institutions, norms, and shared values matter. But even these perspectives acknowledge that hard power still plays a role especially when diplomacy fails.

Historical Examples of Hard Power

1. The U.S. Invasion of Iraq (2003): The U.S.-led invasion of Iraq is a textbook example of hard power in action. The United States, deceptively asserting that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction and posed a threat, launched a full-scale military operation to depose him.

While soft power narratives (democratization, liberation) were used, the primary mechanism was brute military force. The result was regime change, but the long-term consequences in the form of regional instability and turmoil demonstrates the harmful consequences of hard power.

2. Soviet Control over Eastern Europe (1945–1989): Following World War II, the Soviet Union established dominance over Eastern Europe using military occupation and political coercion. States like Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia were kept in line through force, as seen in the crushing of the Hungarian Revolution (1956) and the Prague Spring (1968). The Soviet use of hard power ensured loyalty but bred resentment.

3. China's Military Posturing in the South China Sea: China has used military installations, island-building, and naval patrols to assert its claims over disputed waters in the South China Sea. While China also engages in diplomatic and economic outreach (soft power), its coercive tactics—threatening neighboring countries like the Philippines or Vietnam—demonstrate its willingness to use hard power to pursue national interests.

Economic Coercion as Hard Power

Military force isn't the only form of hard power. In this globalized world, Economic sanctions are increasingly used as instruments of coercion.

1. U.S. Sanctions on Iran: The United States has imposed harsh economic sanctions on Iran over its nuclear program. These sanctions have crippled the Iranian economy, causing inflation, currency devaluation, and unemployment. The aim is to weaken Iran into compliance with Western view which literally is primarily driven by Israel and the Western stereotype that Islam is a survival threat to the west.

2. Russian Energy Leverage over Europe: Before the Ukraine war, Russia used its natural gas exports as a means of influence over Europe. Countries heavily dependent on Russian gas faced implicit pressure to align with Moscow's interests. After 2022, this leverage became a weapon, as Russia cut off supplies to certain countries.

Effectiveness and Limits of Hard Power

While hard power can be effective in achieving short-term goals, it has several limitations:

Backlash: Coercion often breeds resistance. Military occupations can turn into insurgencies.

Cost: War is expensive—financially, diplomatically, and morally.

Soft power erosion: Excessive use of hard power can undermine a state's image and credibility.

Unpredictable outcomes: As seen in Iraq and Afghanistan, even the world’s most powerful militaries can fail to achieve their objectives.

Hard power rarely wins “hearts and minds.” It may secure compliance, but not necessarily legitimacy or goodwill.

Blending Power: The Need for Strategy

In most real-world situations, effective foreign policy blends hard and soft power—what Joseph Nye calls Smart power. For instance:

U.S. Post-WWII foreign policy in Europe mixed $13 Billion to rebuild western European economies together with the formation of NATO to avoid spread of communism in the region.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative mixes infrastructure investment (economic soft power) with debt leverage (potential economic coercion).

The U.S. Pivot to Asia involves strengthening military presence while promoting trade ties with the Asian countries.

Understanding when to apply which type of power is crucial. As Nye points out, relying solely on hard power can make a state appear as a “bully” while relying solely on soft power may make it seem “weak.” Smart power requires strategic judgment.

Conclusion

Hard power remains a core component of international relations. In a world where rivalries endure, and diplomacy sometimes fails, states will continue to maintain armies, stockpile weapons, and deploy economic leverage. However, the world is also changing. With the rise of information technologies, global interdependence, and growing awareness of soft power suggest that force alone cannot ensure influence or stability.

Ultimately, successful statecraft requires a deep understanding of when to use pressure, when to persuade, and how to integrate both approaches effectively. In the words of Clausewitz, war may be the continuation of politics by other means. However, in the 21st century, politics must also be the prevention of war by smarter means.

References

Nye, Joseph S. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (2004)

Morgenthau, Hans. Politics Among Nations (1948)

Waltz, Kenneth. Theory of International Politics (1979)

Mearsheimer, John. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (2001)

Realism:

Idealism:

Constructivism:

![[IR3] International Relations in the framework of Realism](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!xOum!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe75c5f53-3b4d-4938-a77e-d9a30e161f56_1280x1280.jpeg)

![[IR4] Can Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) be a Reflection of Idealism in International Relations?](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!56xO!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F26270a3d-cc3b-4716-ae5a-73a3cc868e3e_1200x675.jpeg)

![[IR5] Analyzing Islam as the Anchor of Constructivism in International Relations](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!nJAw!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F82562e1b-a79c-48a6-b2db-3c71bf728710_1024x1024.webp)

It is not easy to defy the hegemonic states. The forward is to become powerful so that you can resist hegemony. I think we can classify the Raashidoon expansion as smart power, a combination of soft and hard power.

MINEGlobal’s articles are captivating and is bringing a new perspective to the discourse.