Philosophy vs. Practice: The View from Above, The Work Below

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it. — Karl Marx

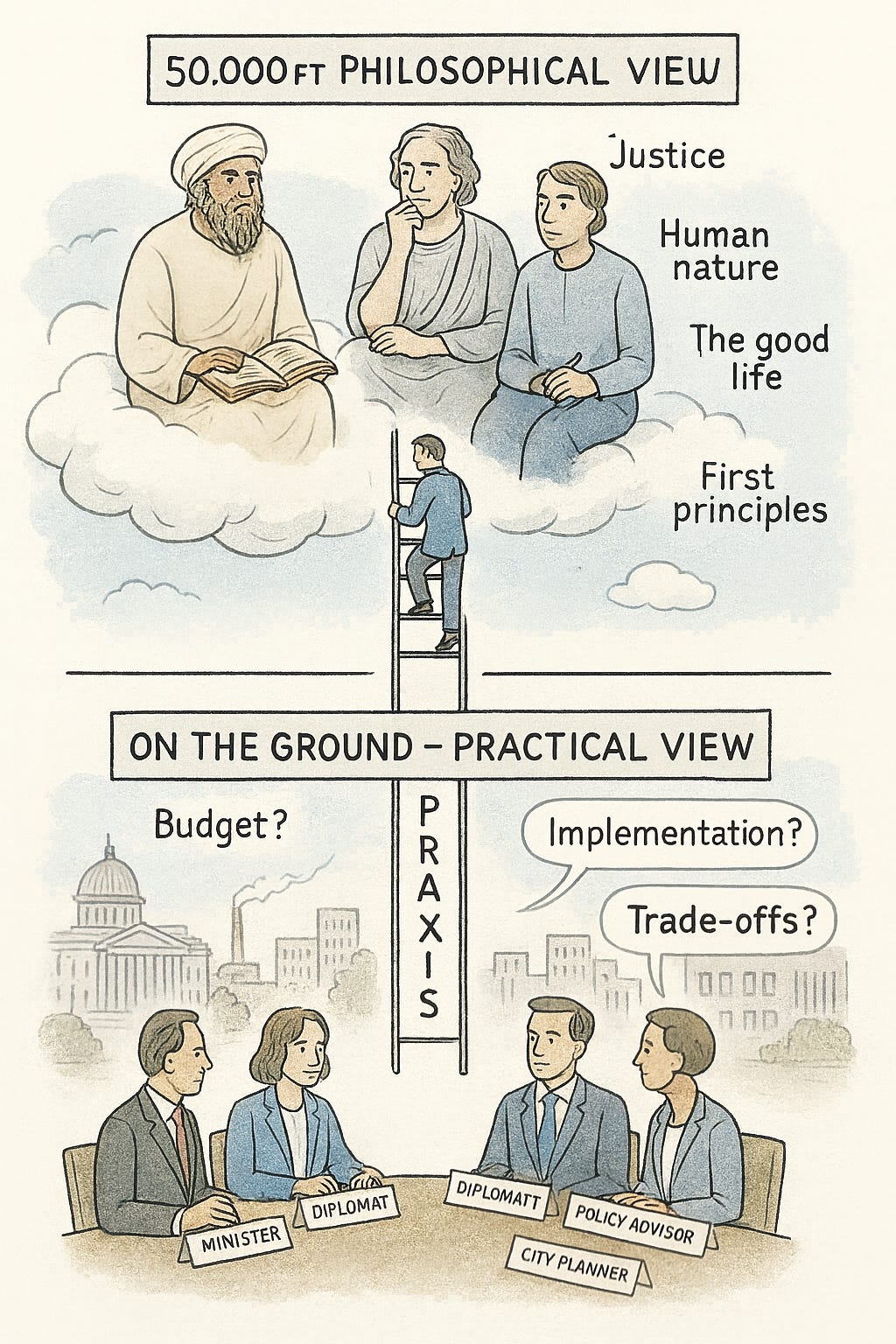

In public policy, economics, governance, and international affairs, the difference between a good and a bad outcome comes not only from ideology or practical solutions, but from the ability to view an issue from multiple levels. Operating at the wrong level of abstraction can mean solving the wrong problem with technical precision or dreaming up grand theories with no path to execution. To truly understand complex systems and effect meaningful change, one must learn to navigate between what can be called the 50,000-foot philosophical view and the 1,000-foot practical view.

These are not simply two types of thinking; they are two levels of vision. One offers holistic breadth, the other depth. The former is based on high-level ideological principles, the latter is determined by immediate constraints. While neither is sufficient by itself, the two together form a dynamic framework for insight and impact.

Philosophy as Foundational Insight (The 50,000-foot view)

The 50,000-foot view is where philosophy operates. It deals with first principles like justice, freedom, equality, responsibility, human nature, and the good life. In Islamic, context we have the Maqasid-e-Shariah (i.e. preservation of Life, Religion, Intellect, Lineage/Progeny, Property).

At this level, the discussion is NOT about policy margins or diplomatic tactics; it is about questions such as: Why should there be a state at all? What legitimizes authority? etc.

Historically, this view has underpinned revolutionary moments in human history. Consider the American Revolution. The immediate conflict centered on taxation and representation, but the deeper motivation was rooted in Enlightenment political thought. Think of John Locke, whose writings on natural rights, property, and consent influenced colonial thinking, and of the republican concepts drawn from Cicero and Cato’s Letters, which shaped the intellectual climate that made independence imaginable. Jefferson and Washington did not invent these ideas. They translated a higher philosophical tradition into a framework for action. Similarly, the U.S. Constitution reflects Montesquieu’s principle of separation of powers, with elements of popular sovereignty that later political thinkers, like Rousseau, helped articulate.

These were not empirical conclusions drawn from observation; they were normative claims about how societies ought to be structured. In other words, at this level, the focus is on what should count as legitimate or desirable in the first place.

Practice, Policy, and Constraints (The 1,000-Foot View)

At the 1,000-foot level, abstract principles descend into the domain of the measurable and the feasible. This is where bureaucrats draft regulations, economists run models, diplomats write treaties. This is where data matters, where the feasibility of good intentions is tested, and where unintended consequences are carefully evaluated.

While philosophy can tell us that inequality is unjust, it is only through the practical work of economics and governance that we determine how to reduce it, what tax policies are effective, what forms of redistribution avoid dependency traps and capital flight in a globalized world, and what trade-offs exist between equality and freedom.

Take the New Deal under Franklin D. Roosevelt. Coming out of Great Depression (of 1929), the high-level idea of protecting the vulnerable, restoring dignity, and restructuring capitalism was influenced by religious ethics and the pragmatic philosophy of John Dewey. But the execution happened at ground level through work programs, Social Security, and banking reforms. The result was an economic and social transformation, but also a recognition that philosophy does not land cleanly. There were many unintended consequences. For example, the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA, 1933) was drafted to provide immediate economic relief to American farmers and to restore stability to an agricultural sector devastated by collapsing prices during the Great Depression. It sought to raise farm incomes primarily by reducing agricultural production and thereby increasing crop prices. But in practice, many landowners evicted tenant farmers and sharecroppers, so a policy designed to help the rural poor ended up hurting some of the poorest people first.

Many policies, designed with good intentions but with unforeseen side effects, were visible during the COVID-19 lockdowns. They led to severe hardships and tragedies, for example the migrant worker crisis in several developing countries, including India, along with rampant inflation. The policy goal was public health, but the lived reality for millions of workers included loss of income, mass displacement, and deep social stress.

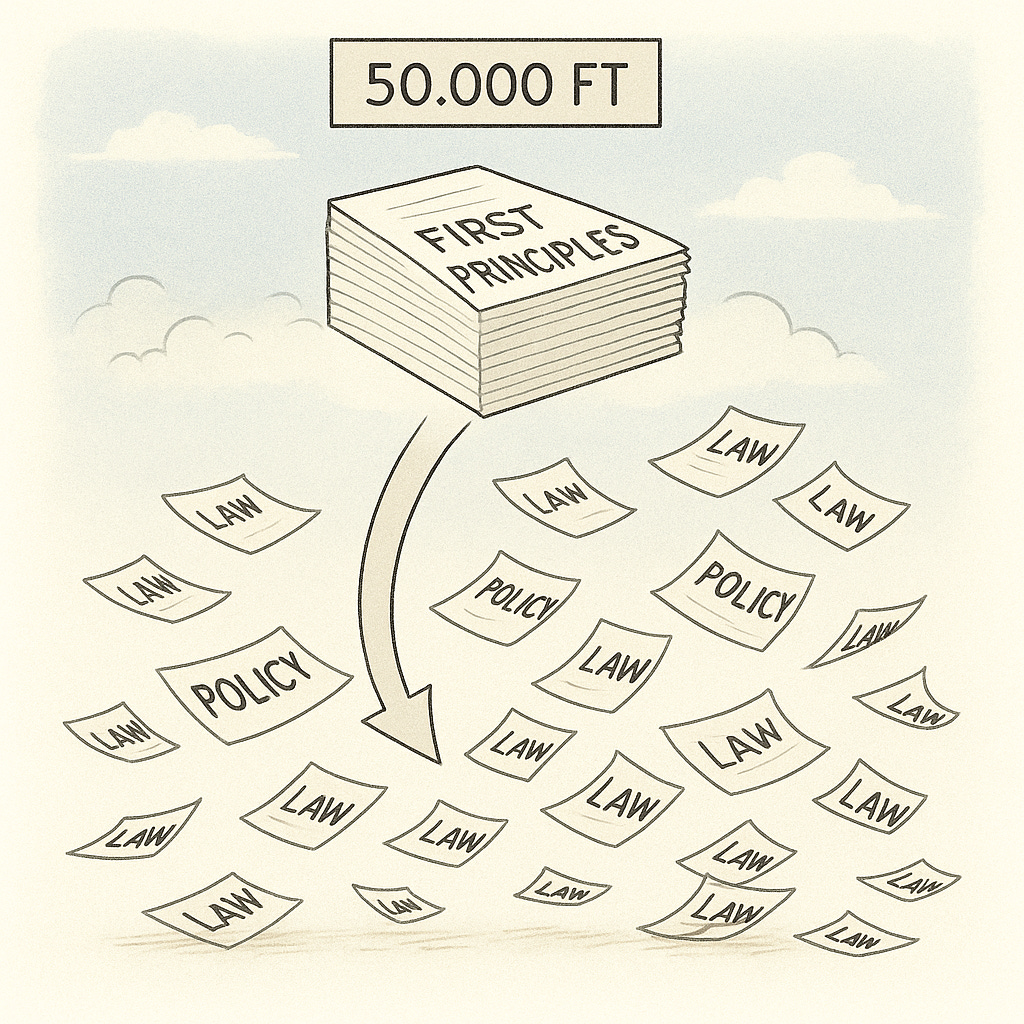

The Broken Descent: Why Philosophy Rarely Lands Pristinely

A critical point is that the 50,000-foot vision almost never translates directly into 1,000-foot outcomes. Grand ideals are filtered through institutions, compromised by interests, warped by culture, and often diluted by the messy realities of practice.

Consider the post–World War II wave of decolonization. Philosophically, it was driven by a powerful vision of national self-determination and anti-imperial justice, influenced by thinkers like Frantz Fanon and Gandhi, as well as the universalist moral framework of the UN Charter. Yet, in practice, many post-colonial states ended up with authoritarian regimes, resource dependencies, or ethnic strife. The philosophical altitude could identify injustice and motivate resistance—but it could not by itself construct stable, just political orders. For example, Algeria’s struggle against French settler colonialism drew part of its moral and intellectual energy from the Islamic reformist writings of Sheikh ʿAbd al-Hamid Ben Badis and the Association of Algerian Muslim Ulama, and later from the anti-colonial thought and activism of Frantz Fanon. After the French withdrew and Algeria gained independence in 1962, however, the FLN-led state soon slid into internal power struggles, culminating in a 1965 military coup and decades of authoritarian rule supported by the army.

The same applies in economics. The Chicago School’s emphasis on free markets is grounded in philosophical liberalism, a belief in autonomy of individuals to grow their business. But in reality, Laissez-faire could produce worst form of injustices and inequality especially when applied universally, say in emerging markets. The “Washington Consensus”, promoted by IMF, led to volatility, inequality, and social unrest in many developing countries despite stated noble goals. Why? Because the real world contains frictions, power asymmetries, and historical legacies that theory, at high altitude, often abstracts away.

The Right Altitude: A Dynamic Perspective

This is why insight and leadership require altitude agility, i.e. the ability to fly high to see the normative landscape and then descend to navigate practical terrain. We need to toggle between:

Philosophy: What is just? What is our purpose?

Practice: What is workable? What are the trade-offs?

The danger of staying at 1,000 feet is short-termism—focusing on metrics without meaning, solving technical problems without asking whether the problem is worth solving. The danger of staying at 50,000 feet is utopian detachment—theorizing without grappling with constraints, or waiting for a pristine world that never arrives.

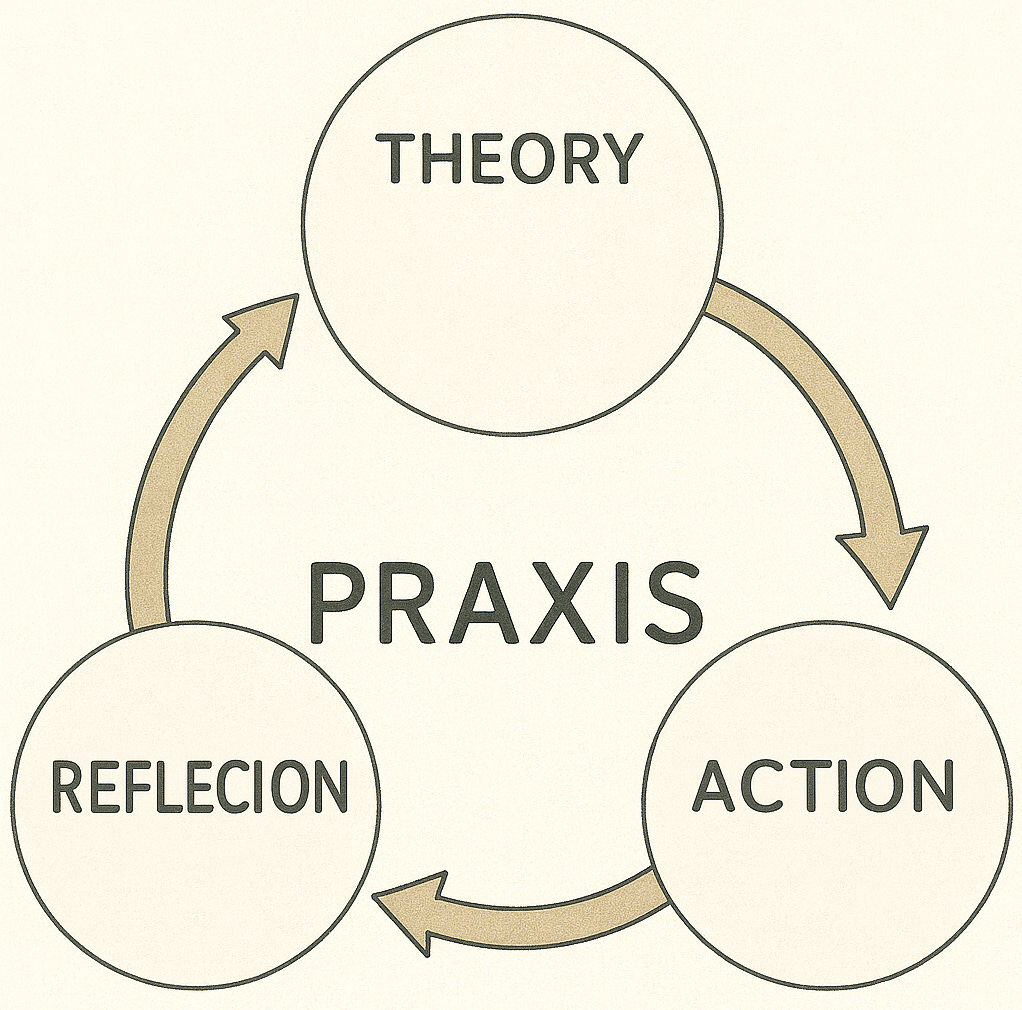

Effective change-makers, policy designers, and intellectuals operate by continually ascending and descending along this vertical axis, engaging in praxis. Praxis is the disciplined movement between the two levels, where we test our values through concrete action, then learn from the results and refine both our ideas and our policies.

One modern day example is Amartya Sen, who moves fluidly between abstract philosophy (his work on justice and capability theory) and applied economics (poverty measurement, development policy). Sen not only ask “What is utility?” but he also develops practical frameworks for how governments should deliver public goods and how to measure well-being beyond GDP.

Why It Matters Today

We live in a time of rapid technological change, rising moral uncertainty, and institutional failures. Technical knowledge alone can’t solve climate change, rebuild trust in democracy, or regulate AI. These are not just engineering or managerial challenges but they are also philosophical problems.

What should we preserve as “human” in an AI-driven world?

What does democratic legitimacy mean in the age of algorithms?

What kind of future are we building and why?

These are high-altitude questions. But answering them requires people who can descend into real systems and understand them with Realism, shape real rules, and anticipate real costs. This practical know-how should then be bubbled up to refine and elaborate the philosophical stance through an exercise in praxis.

“Philosophy gives us the compass. Practice gives us the map. Wisdom lies in knowing when to switch between them.”

From the point of view of Muslim intellectual empowerment, thinking that heavily resides at the 50,000-foot level is highly insufficient and must descend to the ground realities of the 21st-century global order to become effective. Resorting to intellectual escape hatches, such as declaring that the current world order is completely incompatible with Islam or dismissing scholarship on practical matters as slavery to the West or as seeing problems through a “Western lens,” only worsens our already disempowered situation.

The key is not to choose one view over the other, but to move between them with intent. That’s how we understand problems and that’s how we solve them. One of the key objectives of the Muslim Intellectual Network for Empowerment (MINE) is to develop an intellectual platform in which people can move between different levels with ease.

Please join us on Sunday for our presentation on Examining Capitalism: A Balanced Look at Defense and Critique:

"The key is not to choose one view over the other, but to move between them with intent. That’s how we understand problems and that’s how we solve them." - Very important reminder for our Ummah

There should be more talk in the Muslim community about 1000 ft level altitude.