Can We Model Societies? Reflexivity and Its Disruptions

We cannot predict the future course of human history. The future depends on ourselves, and we do not yet know ourselves — Karl Popper, The Poverty of Historicism

Announcement: Alhamdulillah, we launched this publication on June 22, 2024. Since then, our group has produced over 70 posts and more than 200 notes on various topics. We are excited to announce that MINE is rebranding with a new logo and will soon be making the platform more interactive. Stay tuned!

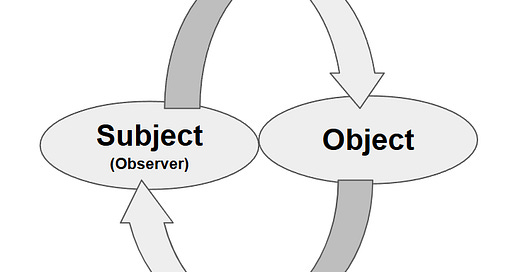

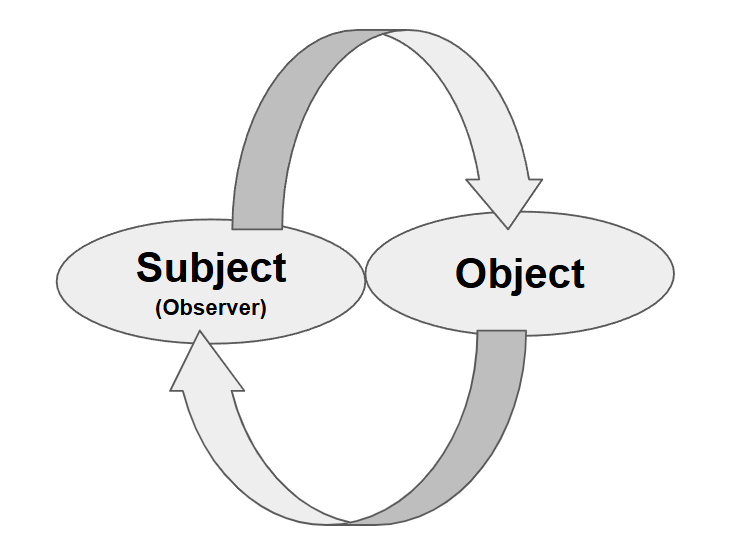

In both philosophy and the social sciences, the subject-object relationship is frequently analyzed and discussed. The two are separated by the distinction that the Subject is the knower or observer, whereas the Object is the thing that the subject observes. In the natural sciences, this relationship is relatively straightforward: the scientist (subject) studies a substance or natural phenomenon (object) from an external and neutral standpoint. The study does not impact the object; for example, Chlorine does not change physically or chemically because a chemist is observing it, nor does the rain intensify because a meteorologist is taking a reading.

However, in the social sciences (such as sociology and economics), this boundary becomes blurred. There are three main problems in dealing with the subject and object in this context:

The observer (subject) and the observed (object) are often part of the same social structure. For example, a sociologist studying class behavior is not outside the social structure but is embedded within it. This jeopardizes claims to objectivity and challenges the assumptions of traditional scientific detachment.

The observer’s act of studying the object can itself alter the object. Anthropologists have long grappled with the fact that their presence influences the behavior or responses of the communities being studied.

When the observer shares their findings with the world (which includes the thinking object), it can influence the observed group’s future behavior, as they consciously or unconsciously adjust their response to how they are represented or understood.

Reflexivity

This complication leads directly to the notion of Reflexivity. In its most general sense, reflexivity refers to the ability to examine and critically reflect upon one's own feelings, actions, and motivations, especially how they influence one's thoughts and actions in a given situation. Reflexivity, for the purpose of current discussion, means that the observer’s humanness (theories, language, and actions) can feed back into and influence the system being studied. This is especially important in economics, where George Soros famously argued that markets are not purely reflective of underlying fundamentals but are shaped by participants’ perceptions and expectations. For instance, if investors collectively believe that a currency will devalue (lose value), their actions (selling off the currency) may cause that very outcome, regardless of the initial fundamentals. Reflexivity challenges the notion of fixed outcome (i.e. causality) and introduces feedback loops between knowledge and action, between model and reality.

Challenges in Modelling

These dynamics become very challenging in modelling human systems. Unlike mechanical or biological models, social models cannot assume a static environment or linear causality (x predictably leading to y). Human systems are interpretative and dynamic, i.e. people change their behavior in response to being studied, to new rules, or to evolving cultural norms. Famous Philosopher, Karl Popper, warned that Human societies are shaped by free will, changing knowledge, and feedback, making them unpredictable. A classic example is the Phillips Curve in macroeconomics, which originally modeled a stable trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

When unemployment is low, inflation tends to rise (because wages increase).

When unemployment is high, inflation tends to fall (due to weak demand).

However, once policymakers began using the model to inform decisions, the relationship broke down, as expectations adjusted and economic behavior changed. When governments tried to reduce unemployment by allowing more inflation, people began to expect prices would rise. Workers asked for higher wages ahead of time, and businesses raised prices to protect their profits. As a result, the original link between inflation and unemployment no longer worked as expected. This is a clear instance of a model losing predictive power due to its influence on the system it intended to describe.

As policymakers and academics rely more and more on elaborate models, reflexivity comes increasingly into play. Social, political, and economic systems in pre-modern times did not use so many models to predict the future, unlike in modern times. This makes predictions very difficult demanding ever-increasing complexity to account for reflexivity. Karl Marx found this out the hard way; his predictions might have come true if the bourgeoisie (capitalists) had continued their course. However, over time, capitalism changed its course and gave workers certain rights and increased compensation, which led to the rise of the middle class and substantially improved the sustainability of capitalism.

In Summary …

To sum-up, the subject-object relationship is far more complex in social inquiry than in the natural sciences, due to the observer's existence within the system. Reflexivity adds further complexity by introducing feedback between knowledge and behavior. These factors combine to make modelling social reality inherently provisional and unstable, demanding continuous revision and a keen awareness of the limits of theoretical frameworks. Predictions of the best of even the best minds might not come to fruition. Policymakers must account for reflexivity by building adaptable institutions that can evolve with public response rather than deterministic theories. Models should guide action, not dictate it, and always be tested against shifting realities. For individuals and societies, the lesson is humility, i.e. understanding that knowledge itself can reshape the world it seeks to describe.